Imran Qureshi was born in 1972 and grew up in Hyderabad, Sindh Province before settling in Lahore, where he is still based. Soft-spoken, thoughtful and deeply engaged with the sociopolitical context of his country, Qureshi talks to Roxanne Bagheshirin Lærkesen in a revealing video for the Louisiana Channel, focusing on his exhibition “Idea of Landscape” at Kunsten in Denmark early last year (23 January to 24 April 2016).

The discussion sheds light on Qureshi’s working processes and his desire to investigate and depict the violence in his homeland. Growing up in Lahore in the 1970s and 1980s, the artist witnessed years of political upheaval and associated bloodshed. However, he says:

I’m not a journalist, my job is not to depict one incident in my art work – it’s all about how things are affecting me […] slowly, slowly, gradually […] and then it comes out of me in the form of my art.

He describes his method of creating art as evolving from whatever is happening around him, but also acknowledges that it is triggered in large part by the 2010 multiple bombings in Pakistan.

Qureshi’s take on traditional miniature painting

Initially, Qureshi concentrated on miniature painting, which is based on decorative, 16th-century Mughal painting. Having studied it at the National College of the Arts in Lahore, he now executes this style with an acknowledged brilliance of craft.

The Guardian critic Laura Cumming described his miniature work at the Ikon Gallery (Birmingham, UK, 2015) as “hauntingly beautiful”. He is part of the Neo Contemporary Miniature Art Movement – a group of contemporary Pakistani artists, including Rashid Rana, Shahzia Sikander and others, who have spearheaded a growing interest in reviving and manipulating historic forms of miniature art.

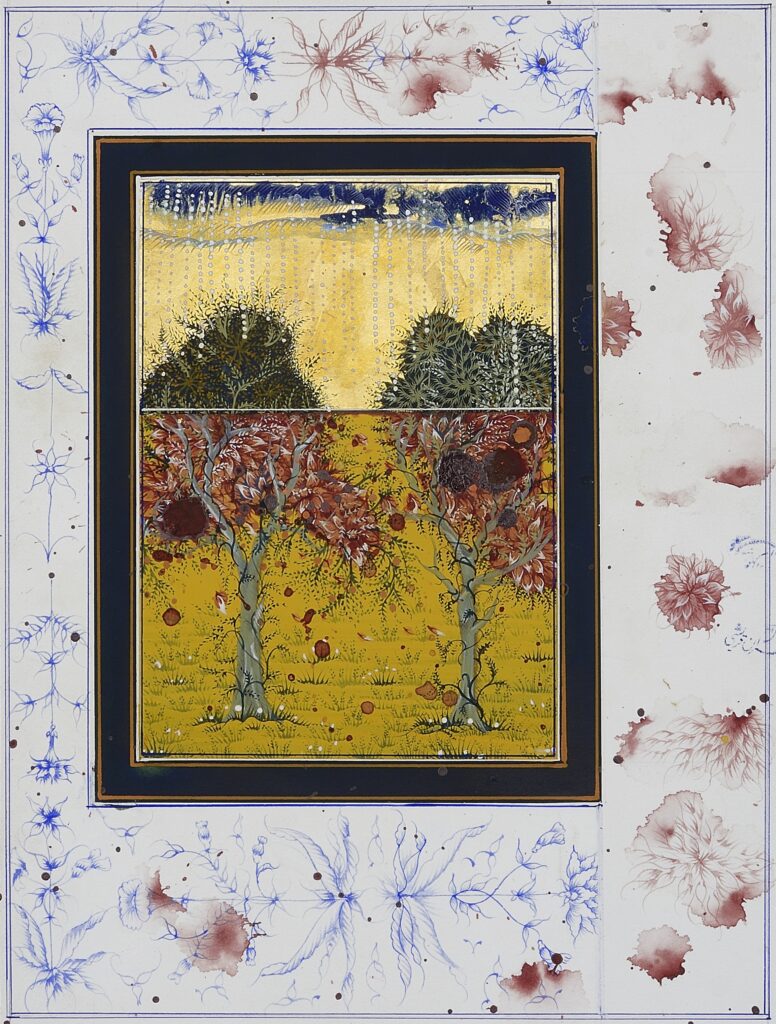

Qureshi’s contemporary interpretation of the discipline is commanding and disturbing. He takes the historic miniature art form and transforms it into a language all his own. The viewer is drawn into the work through its exotic and intricate aesthetic, but up close is confronted with uncomfortable images – violent splashes of dripping red-blood paint, or aggressive daubs of blue which disturb an otherwise calm composition.

He deliberately sets up binary oppositions in his work – beauty and violence, life and death, energy and peace – to interrogate the experience of living in Pakistan today and to offer his own aesthetic perspective on how history interacts with the contemporary. The formal composition of his work, too, is varied and contradictory: large canvases contrast with miniature painting, there are conflicting colour choices, and both figurative and abstract elements often feature within the same works.

Blood on the roof

Qureshi has enjoyed growing attention in recent years. 2013 was a breakthrough year for the artist, in which he received the accolade of Artist of the Year at Deutsche Bank Kunsthalle in Berlin and was also awarded The Roof Garden Commission at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

His installation there covered the entire paved area of the museum’s roof terrace with a dramatic suggestion of violent splashes of blood, but up close, the spattered blood actually consisted of a complex pattern of elaborate stylised flowers – a recurring motif in his work. He explains:

There’s the idea of life, beauty and death working together […]. There is an element of violence in the work. At the same time, when you come close to it and start looking at it carefully, it becomes poetic as well.

Qureshi’s work, whilst arising from the experience of his homeland, is non-geographically specific in its depiction of violence. The New York Times critic Ken Johnson concluded that the artist’s work at the Met delivered a keen emotional impact through this particularly democratic approach:

It remains generously open to meditative reflection. It doesn’t impose a partisan ideology. It’s a place that anyone from anywhere might come to pray for the healing of our wounded world.

Highlights from 2016

2016 could be headlined as Qureshi’s ‘UK year’. He completed three major commissions in the country where his name, not surprisingly, is rapidly becoming well-known. The first was at The Curve at the Barbican, London, entitled “Where the Shadows are so Deep” (18 February to 10 July 2016).

The show regenerated the artist’s fascination for contemporary miniature paintings, executed with perfect draftsmanship and beautifully rendered images. However, he refutes the suggestion that this is a backward-looking art form:

Miniatures aren’t outmoded for me – it’s like I’m talking in my mother tongue.

The Barbican exhibition was a huge undertaking for the artist, including a collection of 35 detailed miniatures, each demanding hours of intense, intricate brush work using the traditional squirrel-hair brush. Curator Eleanor Nairne described the exhibition as an “epic distillation of labour”.

The second UK commission was “Garden within a Garden” in Bradford (22 June to 30 October 2016) as part of the “14-18 Now” World War One Centenary programme. The third featured three linked site-specific installations, supported by Arts Council England, in Truro Cathedral, the Newlyn Gallery and The Exchange, Penzance.

In Truro, Qureshi’s work After which, I am no more I, and you are no more you (27 June to 15 July) was an ambitious project. It featured 30,000 pieces of crumpled paper showing images created by the artist stacked in billowing mounds three metres high and extending from the south aisle to the nave, flowing and spilling over rows of pews. Visitors were encouraged to scrunch up further images and add to the installation.

Current work: Chaos and carnage in Italy

Readers can currently catch Qureshi’s work as Project Fellow at the Siena Art Institute, “The Seeming Endless Path of Memory” at the Civic Museum of San Gimignano, Italy (until 31 January 2017). This gripping installation is exhibited in three stages – the artist’s signature miniature paintings at the base of the Torre Grossa, then ‘bloodied’ images of the artist’s works fill the recesses of the inner walls of the Torre (tower), and, finally, outdoors on the roof of the Civic Museum, a massive floor painting echoing his familiar theme of nature regenerating from chaos and carnage.

In recent years, Qureshi has presented solo shows at the Aga Khan Museum, Toronto; the Broad Art Museum, Michigan; Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris; Nature Morte (with Aisha Khalid), New Delhi; Ikon Gallery, Birmingham; the Sharjah Foundation, Dubai; and exhibited as part of the Venice Biennale 2013. He currently has work in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Qureshi may claim not to be a journalist, but his forensically detailed and emotionally driven work tells us that he is certainly artist as political observer, commentator and interpreter.